The Concept of the Photographer

by Annika Wik, film-theorist

If I use the word photographer, what do you see? Is it a man or a woman? Is it a person who is prominent in the room, or a more discrete and hidden person? Does he or she have a task to complete or is there someone behind the camera ready to capture the moment? In this exhibition six photographers have worked together for a couple of years examining the concept of the photographer. Together they have examined our images of the person behind the camera. They have focused on everything from concrete questions; such as what the photographer looks like, what clothes and attributes are assigned to this person, to more self-reflecting question such as; who do I become in my role as a photographer? Through six bodies of work we encounter different

concepts that have evolved through deepened research analysis and photographic work to artworks. In Sonia Hedstrand’s project we encounter the most toned-down role as a photographer by the way she establishes an intimate relationship with her subject by using hidden cameras. By doing so she joins a large cadre of photographers that have explored their own sexual desires both in front of and behind the camera. By aiming the camera at young Japanese men, her pictures show a less commonly represented image of maleness, while at the same time placing herself as a female photographer in the more traditional role of the male photographer.

Carola Grahn is also challenging conventional concepts. Her crying men come from an exploration of the gender power structure that traditionally has had a significant impact on the history of photography. In Grahn’s images, men risk dropping their surface or lose face. Earlier, Grahn has pointed her camera at men who literally has their pants down. Here, she has taken on men who are weeping. Exposed and revealed, the men are captured in vulnerability. She becomes a witness with her camera, and maybe even guilty.

Björn Larsson’s photo-series Perpetrator also portrays the male role, but this time not focussing on the male himself, but it’s attributes of maleness at front. A long history links the camera and the photographer to someone who ‘captures’ or ’shoots’ someone else, the one where the cameraman or ‘the operator’ uses the camera. We find him with thinkers such as Walter Benjamin or in Luigi Pirandello’s classic text Si Gira! (first published 1916) where both the title and the story refers to the double meaning of ‘Si Gira’, roughly translated as both ‘turn it’ and Hollywood’s more aggressive ‘to shoot’. With cameras designed and shaped like weapons, the image of the photographer doing the latter is amplified as someone with a more aggressive image. Larsson is interested in the inherent symbolism of cameras and camerabags. What does it mean to aim a ‘weapon’ at another being and how can one understand the aspect of photography which is amplified by threatening and war-like attributes? Larsson also creates a link to the pictures by adding a piece of self-made clothing associated with a photo-vest, which is confusingly similar to combat clothing.

The image of the traditional war-photographer as a brave and daring adventurer is contrasted with Isabel Fogelklou’s heavily cropped photographs through which she has recreated the image of a female photographer with a clear assignment. By chance, Fogelklou gained access to the archive of a German photographer who worked for the armed forces in the Germany of World War 2. It’s difficult not to think of another woman whose films contributed to the images of the German war-machine: Leni Riefenstahl. These pictures have not had the same historical impact, but the similarities lie in the assignment to document. The way Fogelklou treats the photographs de-emphasises that assignment while focussing on the supressed emotions that the photographer has captured in the images. The photographer is also in the pictures, but just as with the men and women in

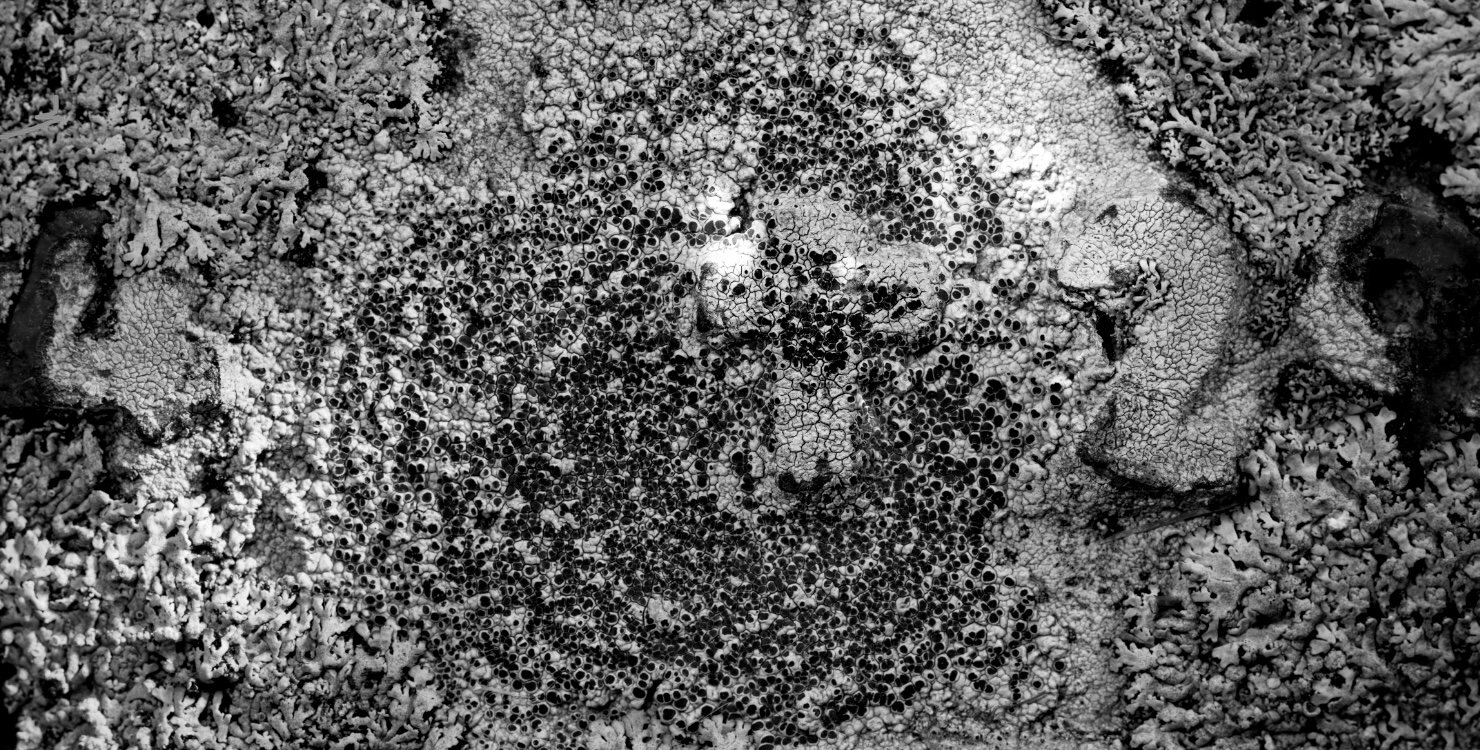

uniform that she has photographed, the heavy cropping of the pictures and hence also the bodies results in the association with individuals becoming lost. The treatment of the images has the effect of dehumanising individuals while at the same time brings out something very threatening in their posture, attitude and the way they hold their hands. It is as if the more she removes the individuals, or brings out the picture’s negative, the more they become portraits of the era when they were taken. Bringing the spectator into the many layers of the picture that Fogelklou does through her appropriation is different from what Oscar Furbacken does. Still, there are similarities. While she strips away to discover emotions in the past, Furbacken steps into his motives as if to reveal an underlying truth. This way he joins a tradition of photographers who believe in the optically unconscious – which is another link to Walter Benjamin. Furbacken is not satisfied with what the camera and the technology can achieve or can do better than the hand. Instead he works to refine and develop tools that can help him reach beyond what the eye can see. By using his self-developed techniques as a photographer, he tries to find evidence to reveal the greatness of nature and the creation.

Leontine Arvidsson uses the camera as an aid, but in her case the camera is more of a helping friend than Furubacken’s helping technologies. During a difficult and confusing period of illness, Arvidsson uses the camera to document her life with breast cancer. In most exposed life’s situations, as a photographer and artist she decides to leave her place behind the camera in the most terrifying way, and amplifies her vulnerability by exposing herself in front of the camera. This shift in position enhances the contradiction of leaving a safe place to reveal one at the most vulnerable situation, while at the same time introducing a droll humour that further shows this contradiction. The self-timer, which ought to be the least obvious of the photographer’s tools, is put to use and in this context symbolises the least common concept about the photographer: the one where the relationship between the photographer and the photographed is completely dissolved.

Together these different photographic series challenges us to assume different positions. As spectators we are invited to have different attitudes to step into different relational practices, between subject and object, between man and machine. Hopefully the exhibition serves to allow us question our own concepts about the photographer, and by extension even the concepts of ourselves. Or as Luigi Pirandelli’s main character, as well as operator, Serafino Gubbio puts it:

"I study people in their most ordinary occupations to see if I can succeed in discovering in others what I feel that I myself lack in everything I do: the certainty that they understand what they are doing."Introduction to Luigi Pirandello’s Shoot: the notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, cinematograph operator.

/Annika Wik

A text by film theorist Annika Wik, written in september 2014 in relation to the project Fotografen presented in the exhibition 3rd Photospectrum: Sweden at Jinsun Gallery in Seoul, Korea.

(financed as an Artistic Development (KU) project by the Royal Institute of Art Stockholm and by Konstnärsnämnden)

Exhibition views from group show at Gallery Jinsun in Seoul 2014